Kaun hai ye gustaakh?

jab wo khaali botal phenk ke kehta hai

duniya! tera husn yahi bad-suurati hai

duniya us ko ghoorti hai

The opening lines above are taken from Majeed Amjad’s poem “Manto”, written after the death of Saadat Hasan Manto. But the question arises: who was Manto? What was he? What force was this name that, even when uttered, could make the so-called respectable members of society frown, as though they had heard something indecent? His stories were branded obscene by some and dismissed as “pornographic tales” by others.

Yet, at the same time, there were people, both in the literary world and outside it, who stood by him and called him “the mirror of society” and “the voice of the voiceless.” To the guardians of morality, however, he always remained a rebel and a blasphemer. Today, let us try to understand: who was this gustaakh (defiant figure)?

Manto was born on 11 May 1912 in the village of Samrala near Ludhiana, Punjab, then a part of British India. His father was a Kashmiri Muslim lawyer, and his family named him Saadat Hasan. At home, everyone called him Manto, without realizing that one day the whole world would know him by that name. “Manto” is originally a Kashmiri name, pronounced in different ways such as Manto, Mintu, or Mantu.

His family lived comfortably, so the early years brought little hardship, and he was able to attend school in Ludhiana with ease. But while admission was secured, the real question was whether Manto had the desire to study. He was lazy by nature, weak in academics, and eventually failed his tenth-grade exams.

In 1933, life changed course for him. Manto met Abdul Bari Alig, a scholar and writer, who awakened in him a love for literature. It was Bari who encouraged him to read Russian and French writers. Manto took this advice seriously and immersed himself in the works of Chekhov, Tolstoy, Oscar Wilde, and Victor Hugo. He read so much that his own literary career began with translations. His first was Hugo’s The Last Day of a Condemned Man, which was published in Urdu under the title Sarguzasht-e-Aseer.

Around the same time, he worked briefly on the editorial staff of the daily Masaawat. In 1934, he wrote his very first short story, Tamasha, which told the story of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre through the eyes of a seven-year-old child. At that moment, Manto himself could not have imagined that his short stories would one day make him both famous and infamous across the world.

In February 1934, Manto moved to Aligarh and enrolled at Aligarh Muslim University for higher studies. At the time, AMU was a hub of leftist thought. There he met poet and communist thinker Ali Sardar Jafri, whose company deeply influenced him. Through this circle, Manto also became associated with the Progressive Writers’ Association.

- Suggested Course

Introduction to Urdu Language, Literature and Culture

The environment in Aligarh intensified his rebellious streak. In fact, he had carried a revolutionary spirit since childhood and considered Bhagat Singh his idol. It was at Aligarh that he wrote his second story, Inqilab Pasand (The Revolutionary), which was published in Aligarh Magazine in 1935. His early stories clearly reflected communist ideas, though with time his writing found its own independent direction.

By 1934, Manto had made his way to Bombay. He began writing for newspapers and magazines and soon entered the Hindi film industry as well. In Bombay, he struck friendships with celebrated personalities such as Noor Jehan, Naushad, Ismat Chughtai, and the actor Shyam. At the time, he lived on Foras Road, a neighborhood in the city’s red-light district. The atmosphere of that place, its realities and struggles, left a visible imprint on his fiction.

In 1936, his first collection of short stories, Atish Paray, was published, containing eight stories.

In 1941, Manto left Bombay for Delhi, where he joined All India Radio. Though he stayed in Delhi for only seventeen months, the period is remembered as the golden chapter of his literary life. During this time, he wrote a series of brilliant radio plays, later published in collections such as Aao, Manto ke Drame, Janazay, and Teen Auratein. He also published his second collection of short stories, Dhuan, along with a controversial volume of essays under the title Manto ke Mazameen.

In July 1942, a clash with the director of All India Radio forced Manto to leave Delhi and return to Bombay. Back in the city, he once again immersed himself in the film industry, and this time wrote some of his most acclaimed screenplays: Aath Din, Shikari, Chal Chal Re Naujawan, and Mirza Ghalib, the last of which was released in 1954. Alongside his work in cinema, he produced some of his most controversial yet celebrated stories, including Kaali Shalwar (1941), Dhuan (1941), and Boo (1945). From this period also came his short story collection Chughad, which included the unforgettable Babu Gopinath.

Manto was fiercely opposed to Partition. He always considered Bombay his home. Yet, the violence of 1947, the bitterness of communal riots, and the heartbreak caused by his dear friend Shyam’s withdrawal of friendship broke something inside him. In January 1948, he decided to leave for Pakistan. Shyam tried hard to stop him. He even argued, “What kind of Muslim are you? You drink, you don’t pray, you don’t fast. Then what are you afraid of here? Why must you go to Pakistan?” Manto’s quiet reply was piercing: “I am at least Muslim enough to be killed in the riots.” By then, his wife and children had already gone ahead to Lahore to stay with relatives. Manto followed by air, leaving Bombay behind.

In Lahore, he soon found himself in the company of poets, writers, and intellectuals who gathered at the famous Pak Tea House, then the heart of literary and political circles. Here he mingled with figures such as Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Nasir Kazmi, and Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi. Yet, Lahore never quite became Bombay. He had no old friends here, no familiar streets, no city that felt like his own. To make matters worse, the Progressive Writers’ Association expelled him, deepening his sense of isolation. To fill this void, he turned more and more to alcohol, a dependency that would eventually claim his life.

At home, Manto lived with his wife Safia, their three daughters, Nusrat, Nighat, and Nuzhat, along with his mother-in-law and a nephew. He continued to write prolifically for newspapers and magazines, producing some of his most enduring stories: Khol Do, Siyah Hashiye, Ganje Farishte, Khali Bottlein, Thanda Gosht, and the masterpiece Toba Tek Singh. But his drinking worsened, leading to constant quarrels at home. In an effort to save him, his family admitted him to a mental asylum, where he spent a considerable period. Though he eventually returned, he could never break free of the addiction, resorting to drinking in secrecy.

In 1954, he penned what is widely regarded as his finest work, Toba Tek Singh, a searing allegory of Partition that immortalized his name. But his health was failing rapidly. On 18 January 1955, at just 42 years of age, Saadat Hasan Manto passed away due to kidney failure, leaving behind a monumental legacy: 22 collections of short stories, a novel, five volumes of radio plays, and two collections of sketches.

Manto and the trials

During his lifetime, Manto was dragged into court six times, accused of writing obscene and immoral stories. Three of these trials took place in British India and three in Pakistan. In India, the cases were filed over Dhuan, Boo, and Kaali Shalwar. In Pakistan, the stories that invited the courtroom’s wrath were Khol Do, Thanda Gosht, and Upar Neeche Aur Darmiyan. Yet, despite the noise, he was never convicted. Only once was he fined a small sum.

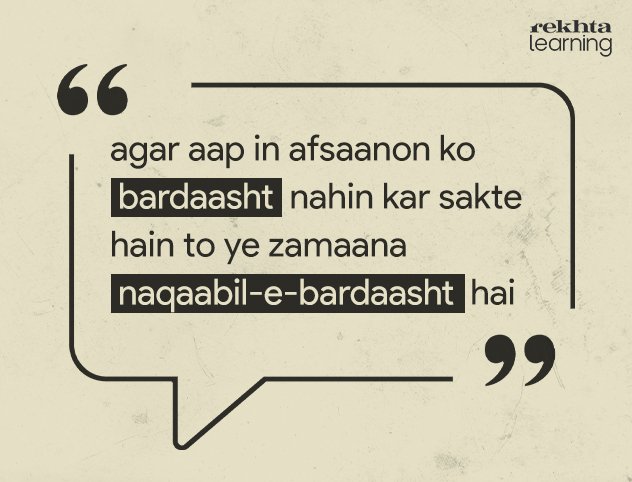

The truth was that Manto’s stories were never obscene. In his own words, they were simply mirrors held up to society. And mirrors, as he often reminded his critics, do not lie.

Why was Manto different?

From the very beginning, Manto stood apart from other writers of his time. While most authors wrote within the boundaries of convention, dressing their tales in refinement and caution, Manto broke those boundaries without hesitation. “Why not write things exactly as they are?” he would ask. And that is precisely what he did.

He wrote about prostitutes when others shied away. He gave voice to their struggles, their grief, their raw humanity. For the so-called respectable classes, this was vulgarity. For Manto, it was truth. His pen was fearless, his gaze unflinching, and his stories drew as much admiration as they did outrage. With every new work, his circle of lovers and haters both grew wider.

Then came Partition, and with it, a wound that cut him to the core.

Manto witnessed riots, killings, lootings, rapes, and displacements with his own eyes. Partition scarred him so deeply that every story he wrote afterward carried its shadow. Few writers in history have chronicled Partition with the same intensity and precision.

Even in Pakistan, he refused to hold back. Through his essays and especially his famous series Letters to Uncle Sam, he questioned where the new nation was headed and whether its future was already in peril. Manto’s audacity to strip society of its pretenses, to expose its rot and its hypocrisies, made him both celebrated and condemned.

And that is why Manto remains different. Bold, uncompromising, and unforgettable.

- 0 in-depth courses

- 0+ lessons

- 1 year unlimited access

- Unbeatable discount

- Watch on any device

- Get certified

.jpg&w=750&q=75)

.jpg&w=828&q=75)

.jpg&w=828&q=75)

Comments