Dastangoi: the traditional art of Urdu storytelling

Urdu is a treasure trove of art forms that have shaped its identity over centuries. From the delicate rhythms of Ghazals to the powerful imagery of Nazms, from the poetic depth of Marsiya to the playful charm of Qawwali, Urdu captures an entire spectrum of human expression. Among these rich traditions, one is Dastangoi, the art of oral storytelling. Once a celebrated form of entertainment in the Mughal era, Dastangoi has a fascinating history that stretches across centuries. Let’s dive into the history of Dastangoi and explore how this lost art is making a remarkable comeback.

What is dastangoi?

Dastangoi is the ancient art of Urdu storytelling, a tradition where stories are not just told, but performed. The word itself comes from two Persian words:

- Dastan – meaning story or tale

- Goi – which means to tell or narrate

At its heart, Dastangoi is more than just narration. It is an art form where the storyteller (Dastango) uses voice modulation, gestures, expressions, and imagination to create a vivid world for the audience. The Dastango doesn’t narrate a story, they make the audience live it.

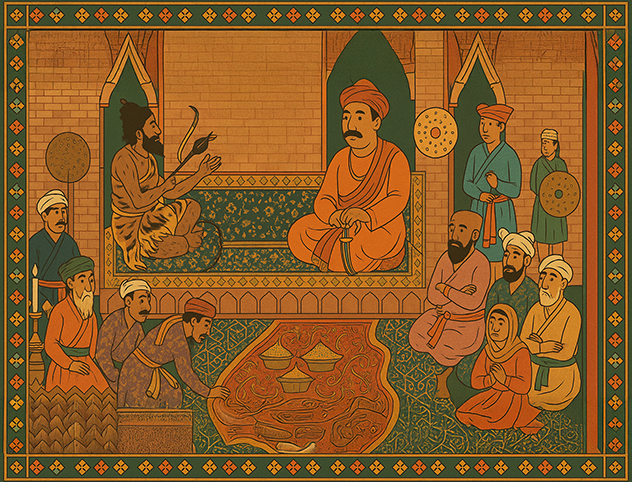

A glimpse into the golden era of dastangoi

Dastangoi as an art form took shape in the 16th century during the Mughal era. It flourished in the royal courts of Akbar and Jehangir, where trained storytellers entertained the emperor and his courtiers with elaborate tales of adventure, romance, and magic. The tales of Dastan-e-Amir Hamza, a legendary Persian story, were particularly popular.

The art of Dastangoi thrived for centuries, especially in the cultural hubs of Delhi and Lucknow. Dastangos would perform in royal courts, public gatherings, and private assemblies. Some of them became celebrities of their time, known for their ability to stretch a single story for weeks, adding new twists and characters depending on the audience's reaction.

- Suggested Course

Introduction to Urdu Language, Literature and Culture

The rise and fall of dastangoi

Dastangoi reached its peak between the 16th and 19th centuries. Delhi and Lucknow were the two great centers of this art form. In the Mughal courts, Dastangos were held in high esteem, and storytelling sessions were considered sophisticated entertainment.

Even after the fall of the Mughal Empire, Dastangoi remained popular among the elites of Lucknow. Abdul Halim Sharar, in his book Guzishta Lucknow, described how wealthy families in Lucknow employed personal Dastangos as a mark of social status. Listening to a Dastan after dinner was a common evening pastime.

But the art form began to decline after the British colonial rule tightened its grip on India. The rise of print media, novels, and cinema meant that people started seeking other forms of entertainment. By the early 20th century, only a few Dastangos remained, and when Mir Baqar Ali passed away in 1928, Dastangoi was believed to have died with him.

The revival of dastangoi

For decades, Dastangoi remained a lost art, a relic of the past. But in 2005, a remarkable revival began. The credit goes to Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, a renowned Urdu critic, and his nephew Mahmood Faruqi.

Guided by his uncle’s deep understanding of Urdu literature, Mahmood Faruqi decided to bring Dastangoi back to life. On May 5, 2005, he held the first modern Dastangoi session at the India International Centre (IIC) in Delhi. Mahmood performed selections from Dastan-e-Amir Hamza, and the audience was spellbound.

For many in the audience, it was their first exposure to this ancient art, and they were amazed at how powerful and captivating oral storytelling could be. Mahmood’s success sparked a renewed interest in Dastangoi. Soon, other performers joined the movement. New stories were created alongside the classics, and Dastangoi found a place in literary festivals, and cultural events.

Why dastangoi still matters

Dastangoi isn’t just about storytelling, it’s about preserving a cultural legacy. The language of Dastangoi is rich with Persian, Arabic, and Indian influences. Its rhythm, imagery, and metaphors capture the musicality and beauty of Urdu like no other medium. Dastangoi is not just a performance; it’s a living art form rooted in our history. And that’s exactly why it deserves to be heard, remembered, and celebrated.

- 0 in-depth courses

- 0+ lessons

- 1 year unlimited access

- Unbeatable discount

- Watch on any device

- Get certified

.jpg&w=750&q=75)

.jpg&w=828&q=75)

.jpg&w=828&q=75)

Comments